- Herbal Education History

- Alternative Medicine Classes

- Alternative Medicine History

- Herbal School Foundations

by Candis Cantin, Herbalist, AHG

Over the past decade or so I have taken time to read the history of herbal medicine from various authors, focusing mostly on Egyptian, Greek, Arab, East Indian and Western European roots. What I have found is a rich, colorful and surprising array of characters, circumstances, wars, religions, societies and cultures that have engendered the herbal and medical traditions that we currently have in the modern era.

The study of medical, botanical, and herbal history was in part motivated by what I heard in various alternative medicine/herbal classes and read in publications about the history of these fields. What disturbed me most was how often various herbal ‘tales’ have been spread around without any consideration as to their truth. As one colleague states, ‘Herbal legends abound in our field.’

However, without a somewhat accurate delineation of events, discoveries, interactions of cultures, cultural morays, societal conditions, religious beliefs and so forth, we can fall prey to the agreed upon and many times misquoted and extrapolated statements about our herbal tradition. What I have also found is that many people have become complacent about these ideas and actually begin to believe these misconstrued conceptions.

Without knowing our roots from which herbalism grows from, we can begin to create a story or myth that will favor our own particular angst about our lives, current political views or’scenes’ in which we are involved. We can say, for example, ‘Women have always been suppressed; look at how all the women herbalists were killed at (such and such a time). That is why we almost lost our knowledge.’ Or another statement that I have heard: ‘(This or that healing method) was divinely given to (such and such a tribe), is the oldest form of medicine and that is the end all of it.’ These statements are limiting in their view, usually not true and may lead to a rather rigid philosophic view. Often, these misconstrued ideas are defended with much hubris and those who harbor these views are usually not open to discussion.

But putting things in a historic, bigger picture perspective opens us up to the vast array of viewing our healing art. We will not get so stuck on just one story or way of seeing things. We can be continually amazed at the tenacity of the human experience and our insatiable curiosity as well as our ability to forget what has already been achieved!

It is hard to know just where to begin this type of paper as the subject is so vast; with cultures rising, ending, melting into other cultures, wars, religious feuds, the forgetfulness of cultures, the rediscovery of information after the forgetting, the superstitions, the world views of certain time periods, and on and on.

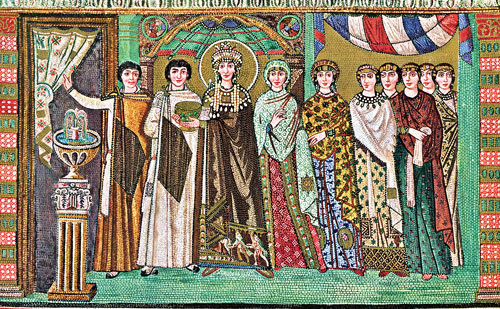

The other difficulty encountered in delineating this subject is that at certain points in history, people are having vastly different experiences. For example, our modern day experience as Americans is vastly different from a refugee’s experience in Syria in the same year. Historically speaking, I hear people making statements like, ‘During the Dark Ages the medicine and learning was stagnant.’ First, what time period are we talking about, and secondly, what area of the world are we referencing? Yes, in 600 AD things were very stagnant and superstitious in Western Europe but in the Byzantine Empire there was great learning and expansion of medical/herbal knowledge.

So let’s begin our historical journey after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century, (476 AD). At this time and for about 500 years after, Western Europe lost touch with much of its intellectual heritage. Of Greek sciences, all that remained were Pliny’s Encyclopedia (Pliny died in 79 AD in Pompeii. He wanted to see what was happening with the volcano so sailed there and perished from the fumes), and Boethius’s treatises on logic and mathematics. The Latin library was so limited that European theologians found it nearly impossible to expand their knowledge of their own scriptures (Latin was the common language of the learned and theologians).

BYZANTINE EMPIRE

However, at the same time, the Eastern Roman Empire became the successor state to the Western Roman Empire. The empire was named Byzantium and was named after the ancient city of Byzantium, located on the site of current day Istanbul. Constantine I rebuilt the city in 330 AD as his capital and named it Constantinople.

The Roman Empire had split permanently in 395 AD into East and West due to theological differences, but after the Western Empire fell (476 AD), the Eastern Empire claimed the entire Roman world. Boundaries shifted, but the core of the Byzantine Empire was Asia Minor (current day Turkey) and the Southern Balkan Peninsula (Greece and surrounding areas). Throughout its 1,000 years of existence, the empire was continually beset by invaders and internal religious and political strife. Nevertheless, despite a complex administration, gross violence, and moral decay, the empire carried on the Greco-Roman civilization, blended with Middle Eastern influences, while the West was in chaos. Through centuries of turmoil, wars, schisms, and finally being encircled by the Ottoman Turks, Constantinople fell in 1453 to Muhammad II. Our modern era is traditionally reckoned from that date. The Byzantine Empire was Greek in nature and the common language was Greek and the religion was Christian Orthodoxy.

In spite of all the turmoil, Byzantine medicine was practiced throughout the Byzantine Empire from about 400 AD to 1453 AD.

As stated, for approximately 500 years, Western Europe’s medical and herbal roots stagnated and were beset with superstition, but the Eastern Roman Empire and its herbal medicine flourished. It drew largely on Ancient Greek and Roman knowledge from books that were preserved in its extensive library. However, medicine was also one of the few sciences in which the Byzantines improved on their Greco-Roman predecessors. As a result, we shall see how Byzantine medicine had a significant influence on Arab medicine and the Western rebirth of medicine during the Renaissance as our story unfolds. When I use the word ‘medicine’ in this text I am referring to the use of herbs of all sorts, minerals, and animal parts.

Byzantine physicians often compiled and standardized medical knowledge into textbooks. These books tended to be elaborately decorated with many fine illustrations, highlighting the particular ailment. The Medical Compendium in Seven Books, written by the leading physician Paul of Aegina, is of particular importance. The compendium was written in the late seventh century AD and remained in use as a standard textbook for 800 years.

Late antiquity witnessed a revolution in the medical scene and many sources mention the establishment of hospitals; Constantinople doubtless was the center of such activities in the Middle Ages, owing to its geographical position, wealth and accumulated knowledge.

ROOTS OF ANCIENT GREEK MEDICINE

A Very brief overview

The medicine of Western Europe and Byzantium was engendered by the medicine in ancient Greece which in turn was influenced by Babylonian and Egyptian medicinal traditions. The ancient Greeks developed a humoral medicine system where treatment sought to restore the balance of humours within the body. They used many different formulas for creating a balance with the humors or the elements of earth, water, fire and air.

A towering figure in ancient Greek medicine was the physician Hippocrates of Kos, 460 ‘“ 380 BC, considered the “father of modern medicine.” The Hippocratic Corpus is a collection of around 70 early medical works from ancient Greece strongly associated with Hippocrates and his students. Most famously, Hippocrates invented the Hippocratic Oath for physicians, which is still relevant and in use today.

Hippocrates and his followers were first to describe many diseases and medical conditions. He is given credit for developing critical thinking within the medical field and trying to see the causes of disease using observation and logic. He tried to eliminate superstition and other-worldly causes of diseases, finding these ideas to be neither efficacious, nor helping to relieve the conditions he faced in his patients.

Pandonios Dioscorides (77AD) was for the next 1500 years revered as the ultimate authority on plants equally in both the Eastern Arab Empire and Western Europe. Dioscorides wanted to produce a decent field guide to plants useful in medicine and wanted a way of retrieving easily the kind of information he required to treat his patients. Dioscorides is one of the first people to point out that, ‘Anyone wanting experience in these matters must encounter the plants as shoots newly emerged from the earth, plants in their prime, and plants in their decline. For someone who has come across the shoot alone cannot know the mature plant, nor if he has seen only the opened plants can he recognize the young shoot as well.’ He drew on local knowledge and traditions, and also mentioned previous authors such as Theophrastus (300 BC ‘“ who tried to sort out plant families, felt that the superstitions around plants were not to be used and generally tried to categorize the plants in a sort of observable order). He divides the information into five books covering the following:

- oily and resinous plants useful for making aromatic salves and ointments

- trees and shrubs that produce raw materials useful in Medicine

- cereals

- pot herbs

- sharp aromatic herbs

He writes about the importance of roots and the juices extracted from them. He also lists the seeds that have medicinal properties and makes an inventory of the various wines and cordials he has found useful in treating patients.

Later in Roman times the Greek physician Galen (2nd century AD) was one of the greatest surgeons of the ancient world and performed many operations, including brain and eye surgeries, that were not tried again for almost two millennia. He wrote prolifically, identified many herbs growing in various locations, and unfortunately developed a more rigid version of the humoral system of medicine, but generally contributed greatly to the inquiry of herbal medicine/ wound healing and surgery.

EUROPE IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

During the early Medieval Ages (5th ‘“ 9th centuries) in Europe, medicinal knowledge was chiefly based on surviving Greek and Roman text, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere. Ideas about the origin and cure of disease were not, however, purely secular, but were based on a spiritual world view, in which factors such as destiny, sin, astral influences, demons, possession, curses, and will of the gods took greater precedence in causation than any physical cause. One author dubs this the ‘shamanistic complex’ and ‘social consensus.’ The efficacy of cures was similarly bound in the beliefs of patient and doctor rather than empirical evidence, so that physical remedies were often secondary to spiritual intervention.

The center of Europe’s new world view became the Church, which exerted profound new influences in medicine. Because Christianity emphasized compassion and care for the sick, monastic orders ran fine hospitals’”but they did not function as hospitals do today. They were simply places to take seriously ill people, where they were expected to either recover or die as God willed. There were very few or no learned physicians to attend them, only kindly monks who dispensed comfort and the sacraments, and various herbal medicines.

Because the Christian Church viewed care of the soul as far more important than care of the body, medical treatment and even physical cleanliness were little valued, and mortification of the flesh was seen as a sign of saintliness. In time, nearly all Western Europeans came to look upon illness as a condition caused by supernatural forces, which might take the form of diabolical possession. Consequently, cures could only be affected by religious means. The Church at this time wielded great influence on all aspects of life.

In a way very similar to very ancient medicine, every malady had a patron saint to whom prayers were directed by the patient, family, friends and the community. Upper respiratory infections were warded off by a blessing of the throat with crossed candles on the feast of Saint Blaise. Saint Roch became the patron of plague victims. Saint Nicaise was the source of protection against smallpox. Kings, regarded as divinely appointed, were believed to be able to cure scrofula and skin diseases, among other maladies, with the “royal touch.”

In early societies of Egypt, India, China, and Greece, this ‘magical’ thinking was prevalent and incantations and rituals were performed to ward off evil. In fact, crop failures, bad weather, pandemics and other disasters were many times seen as being caused by a group of people or sometimes a single person who displeased God (or the gods). Usually some sort of atonement had to be made. Vestiges of this still abound in various religious communities today.

In modern times, these prayers or ceremonies can have a soothing effect and may help greatly in the healing process but may not necessarily allay the illness or condition at hand. A medical diagnosis is needed for many serious and un-resolving issues. Without the understanding of the cause of the condition due to a lack of diagnosis or wrong diagnosis or prayer only, the condition can sometimes be prolonged or even grow worse. This is not to debunk the use of intention, prayer and positive thought at all, but to rely exclusively on this can be a disservice to the patient.

At this time in Europe, licensed medicine as an independent craft virtually vanished. Those physicians who endured were mostly connected with monasteries and abbeys. But even for them, the generally accepted goal was less to discover causes, or even to heal, than to study the writings of other physicians and comment on their work. In the middle of the seventh century, the Catholic Church banned surgery by monks, because it constituted a danger to their souls. Since nearly all of the surgeons of that era were clerics, the decree effectively ended the practice of surgery in Europe. Critical thinking was not understood nor taught at this time in Europe. (Hippocrates, Aristotle and other Greeks had made great strides in scientific/critical thinking but this was lost to Western Europe during these centuries.) The discussions on illness and life were all theologically based with no or little outside scholarly influence. This was the dark ages of the soul of Europe.

As an aside, I have seen modern herbalists and healers try to implement some of these early medieval ideas in their practices but it must be remembered that most of the common people of this time were not educated, were extremely superstitious, and were given many oppressive ideas about their life, the afterlife and the way in which they were to conduct themselves. One can implement these ideas if that is part of the religious belief but don’t throw out the tried and true diagnostic techniques of, for example, Chinese, Ayurvedic and Western medical traditions.

ARAB INFLUENCES

‘Read in the Name of Allah.’ –Koran

Now we will embark on a journey and see how the Arabs saved and expanded on the medicine and sciences of the Greeks. While Western Europe was sinking into a deep black hole, there was a renewal of the intellectual life in the East.

We will begin our story at the ancient and beautiful city of Jundi Shapur. In 490 AD, its benevolent king had sheltered excommunicated Nestorian Christian scholars from Europe ‘”among them physicians. The Nestorians were followers of Nestorios, a tough patriarch in the Roman Empire, who had been excommunicated for heresy.

However, before settling in Jundi Shapur, his followers first went to live with erudite monks in Edessa, Syria. Originally founded as a Macedonian colony, Edessa was well placed on the northern edge of the Syrian plateau both for those traveling on the north-south trade route and the east-west routes, the Silk Road to China. There had been a medical school in Edessa since the fourth century where the Nestorians now taught and worked.

When in 489 AD the Emperor Zeno declared it a hotbed of heretics, the hospital was closed and the Nestorian teachers moved to Nisibis, and then on to Jundi Shapur in Persia, north of the Black Sea. Jundi Shapur also welcomed the neo-Platonists after Plato’s school was closed in 529. Other Nestorians went as far east far as India and China where they settled.

The Nestorians, being scholars, began the huge bibliographic task of translating Greek books into Syriac, the language of the university. Hippocrates and Galen were among their first translations.

The adventures of the Nestorians explain why some Greek works have come down to us ultimately as Latin versions from an Arabic text translated from the Syriac. The Nestorian experience also explains why the great Arabic physicians Rhazes, Avicenna and Albucasis not only revered the Greek masters but spoke their same words and tempered them with East Indian medicine.

Back to Jundi Shapur. Most people have never heard of it but it was a pivotal place in the preservation and promotion of knowledge. When the city fell to the Arabs in 636, and Persia became part of the Islamic world, the university was not disturbed. In fact, the conquerors adopted it and made its medical school their principal training center.

The rulers of Jundi Shapur welcomed an international crowd of Greek, Persian, Jewish, and Hindu scholars. This convergence created the greatest center of medical teaching in the Islamic world for hundreds of years. People of all creeds worked together in peace, as nowhere else in the world.

While the Arab physicians first familiarized themselves with the works of Hippocrates, Galen and other Greek physicians (many books were found in the library of Byzantium were they where gathering dust), they also were exposed to the medical knowledge of India and China. Scholars, physicians, astronomers, and intellectuals of all branches of knowledge were encouraged to debate, study and write about their work in this benevolent setting.

Toward the end of the 10th century, Baghdad, having become the capital of the caliphate, began to drain away the talents of Jundi Shapur. In consequence, the end came fast. Today, nothing remains of that glorious city except for a few vague trenches in the ground.

It must be noted that many of these scholars were plant men as well and were involved in adventurous exchanges of plants from different countscries and locals which helped expand the existing material medica. The Islamic Empire eventually stretched from Spain, Italy, Central Asia, North Africa to the whole Middle East allowing for the plant exchanges to be vital and exciting.

BAGHDAD

Recognizing the importance of translating Greek works into Arabic from the Syriac to make them more widely available, the Abbasid caliphs Harun al-Rashid (786-809) and his son, al-Ma’mun (813-833) established a translation bureau in Baghdad, called the House of Wisdom. This ushered in an even greater era in Arabic medicine, whose effects we feel today. This is considered the great period of translation and compilation. This explosion of inquiry, experimentation, development of all the sciences was a very different world from its Western European counterpart of this time. This was the Golden Age of the Arab world.

The most important of the translators was Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-‘Ibadi (809-73), who was reputed to have been paid for his manuscripts by an equal weight of gold. He and his team of translators rendered the entire body of Greek medical texts, including all the works of Galen, Oribasius, Paul of Aegin, Hippocrates and the Materia Medica of Dioscorides, into Arabic by the end of the ninth century. These translations established the foundations of a uniquely Arab medicine.

Arab medical practice largely accepted Galen’s premise of humors, which held that the human body was made up of the same four elements that comprise the world: earth, air, fire and water. These elements could be mixed in various proportions, and the differing mixtures gave rise to the different temperaments and “humors.” When the body’s humors were correctly balanced, a person was healthy. Sickness was due not to supernatural forces but to humoral imbalance, and such an imbalance could be corrected by the doctor’s healing arts.

Arab physicians therefore came to look upon medicine as the science by which the temperaments of the human body could be discerned and to see its goal as the preservation of health and, if health should be lost, there was assistance in recovering it. They viewed themselves as practitioners of the dual art of healing and the maintenance of health.

Even before the period of translation closed, advances were made in other health-related fields. Harun al-Rashid established the first hospital, in the modern sense of the term, at Baghdad in about 805. Within a decade or two, 34 more hospitals had sprung up throughout the Arab world, and the number grew each year. These hospitals were amazing places judging from the descriptions left to us.

These hospitals bore little resemblance to their European counterparts as mentioned earlier. The sick saw the hospital as a place where they could be treated and perhaps cured by physicians, and the physicians saw the hospital as an institution devoted to the promotion of health, the cure of disease, and the expansion and dissemination of medical knowledge. Medical schools and libraries were attached to the larger hospitals, and senior physicians taught students, who were in turn expected to apply what they had learned in the lecture hall to the people in the wards. The hospital treated all people ‘“ rich and poor alike ‘“ and those of different religious beliefs. There were gardens, music, reading of the Koran, and rather than having a huge bill for the services rendered, the destitute were given money when they left the hospital so that they could live a little more comfortably while they continued to heal.

Hospitals set examinations for their students, and issued diplomas. By the 11th century, there were even traveling clinics, staffed by the hospitals that brought medical care to those too distant or too sick to come to the hospitals themselves. The hospital was, in short, the cradle of Arab medicine and the prototype upon which the modern hospital is based.

Like the hospital, the institution of the herbal pharmacy, too, was an Arab development. Islam teaches that “God has provided a remedy for every illness,” and that people should search for those remedies and use them with skill and compassion.

One of the first pharmacological treatises was composed by Jabir ibn Hayyan (ca. 776), who is considered the father of Arab pharmacy. The Arab pharmacopoeia of the time was extensive, and gave descriptions of the geographical origin, physical properties and methods of application of everything found useful in the cure of disease (plants, minerals, animals, insects and so forth). Arab pharmacists introduced a large number of new drugs (herbs) to clinical practice from around the known world. Some of these were senna, camphor, sandalwood, musk, myrrh, cassia, tamarind, nutmeg, cloves, aconite, ambergris and mercury.

The pharmacists also developed syrups and juleps ; the word ‘julep’ comes from both Arabic and Persian languages, meaning a sweet water made from such things as rose water and orange blossom water as means of administering drugs. They were familiar with anesthetic effects of some of the Indian herbs as well that were added to liquids or inhaled.

At this time the pharmacist was a profession practiced by highly skilled specialists. They were required to pass examinations, be licensed, and were then monitored by the state. At the beginning of the ninth century, the first private herbal apothecary shops opened in Baghdad. Pharmaceutical preparations were manufactured and distributed commercially, then dispensed by physicians and pharmacists in a variety of forms’”ointments, pills, elixirs, confections, tinctures, suppositories and inhalants. Herbal medicines were reaching a new level of use and appreciation at this juncture in history.

REVIEW and EXTENSION

At first, the Arabs translated, compiled and studied the ancient Greco-Roman texts from the Greek to Syriac and then to Arabic, and developed centers of learning where people from Persia, India, North Africa, China and escapees from Western Europe could come together to exchange insights and ideas about medicine and the sciences in general.

By 800 AD, this explosion of information over time was infused with original thought in Arab medicine. The first major work showing this fusion appeared when Al-Razi (Rhazes) around 841-926 turned his attention to medicine. His most esteemed work was a medical encyclopedia in 25 books, The Comprehensive Work, later translated into Latin. Al-Razi spent a lifetime collecting data for the book, which he intended as a summary of all the medical knowledge of his time, augmented by his own experience and observations. Al-Razi emphasized the need for physicians to pay careful attention to what the patients’ histories told them, rather than merely consulting the authorities of the past. Al-Razi’s clinical skill was matched by his understanding of human nature, particularly as demonstrated in the attitudes of patients.

In a series of short monographs on the doctor-patient relationship, he taught that doctors and patients need to establish a mutual bond of trust. He felt that positive comments from doctors encourage patients, made them feel better and sped their recovery; and, he warned, changing from one doctor to another wastes patients’ health, wealth and time. I think this principle of doctor/patient relationship should be heeded by our current medical professionals as well. As herbalists also it is important to remember how our clients build trust in us over time as we enter their world and story. I have found that over the past 25 years of being in practice that I have many clients who trust my work due to the long term relationship that we have built upon.

AVICENNA OF CENTRAL ASIA

Not long after Al-Razi’s death, a Persian named, Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn ‘Abd Allah ibn Sina (980-1037) was born in Bukhara, in what today is Uzbekistan in Central Asia. Later, translators Latinized his name to Avicenna. He was to the Arab world what Aristotle was to Greece and what Leonardo da Vinci was to the Renaissance. His interests embraced not only medicine, but also the fields of philosophy, astronomy, science, mathematics, psychology, music, poetry and statecraft. His contemporaries called him “the prince of physicians.”

Avicenna was the son of a tax collector. He was so endowed with such brilliance that he had completely memorized the Koran by age 10. Then he studied law, mathematics, physics, and philosophy. At 16 he turned to the study of medicine, which he said he found “not difficult.” By 18, his fame as a physician was so great that he was summoned to treat the Samanid prince, which he did successfully. Because of this he was granted access to the Samanid royal library, one of the greatest of Bukhara’s many storehouses of learning.

Avicenna created an extensive body of works during what is commonly known as The Arab Golden Age, in which the translations of Greco-Roman, Neo- and Mid-Platonic, and Aristotelian texts were commented on, revised and developed substantially by Arab intellectuals. Over his lifetime Avicenna wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. In particular, 150 of his surviving treatises concentrate on philosophy and 40 of them concentrate on medicine and herbs.

Avicenna is also regarded as a pioneer of aromatherapy because of his invention of steam distillation and extraction of essential oils which he used in his practice.

His most profound contribution to medicine was his medical encyclopedia called The Canon of Medicine, originating around 1025 in Persia.

The Canon of Medicine is known for its introduction of systematic experimentation and the study of physiology, the discovery of contagious diseases and sexually transmitted diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of infectious diseases, the introduction of experimental medicine, clinical trials, and the idea of a syndrome in the diagnosis of specific diseases. Avicenna hypothesized the existence of microorganisms and classified and described diseases, and outlined their assumed causes. Hygiene, simple and complex medicines, and functions of parts of the body were also covered. He asserted that tuberculosis was contagious, which was later disputed by Europeans, but turned out to be true. He also describes the symptoms and complications of diabetes as well.

I have to remind the reader, when the word’ medicine’ is used in this text it is the herbal plants, minerals and animal parts that were used. Do not confuse the term medicine with our modern concept of this term. The Canon includes a description of some 760 medicinal plants and the medicine that could be derived from them. At the same time Avicenna laid out the basic rules of clinical drug trials, principles that are still followed today. Avicenna was, in fact, a great herbalist.

Not surprisingly, The Canon rapidly became the standard medical reference work of the Arab world. The Canon was used as a reference, a teaching guide and a medical textbook until well into the 19th century, longer than any other medical work. This healing system is referred to as Unani Tibb which translated means the ‘Medicine of the Greeks’ and is still in practice today in India, Central Asia and the Middle East.

The civilized and intellectually advanced Arab scholars of the 12th and 13th centuries continued to develop and elaborate the study of medicine far beyond the point where their Greek mentors had left it. They traveled widely, they drew on their own observations and they organized expeditions specifically to look at and identify plants. In their herbals we see teasel, chamomile, artemisia, umbellifera, elder, horsetail, euphorbia, lesser celandine, elecampane, coral, and so much more. It would be a couple of centuries before this type of botanical expedition would happen in Western Europe.

EUROPE REAWAKENS

During the 12th century, Europe began to reap the intellectual riches of the Arabs and, in so doing, sought out its own classical heritage. The works of the Greeks and Romans had been preserved and expanded upon by the Arab scholars and physicians and was now making a complete loop back to Europe. The medical works of Galen and Hippocrates returned to the West by way of the Middle East and North Africa, and the Arab Medical classics were translated into Latin, the common language of the educated class in Europe. Through the intellectual ferment of the Arab scholars and intellects, Europe recovered some of its past.

There were two main translators of classical material from Arabic into Latin. One was Constantine the African (who spoke and studied three languages fluently) (1020-1087). He worked at Salerno and in the cloister of Monte Cassino. The other translator was Gerard of Cremona (1140-1187), who worked in Toledo. It was no accident that both these translators lived in the Arab–Christian transition zones, where the two cultures influenced each other. And it was no coincidence that Salerno, Europe’s first great medical school of the Middle Ages, was close to Arab Sicily.

Avicenna’s Canon made its first appearance in Europe by the end of the 12th century, and its impact was dramatic. Copied and recopied, it quickly became the standard European medical reference work. In the last 30 years of the 15th century, just before the European invention of printing, it was issued in 16 editions; in the century that followed more than 20 further editions were printed. From the 12th to the 17th century, its materia medica was the pharmacopoeia of Europe, and as late as 1537 The Canon was still a required textbook at the University of Vienna. This is the true roots of Western European herbalism.

Contemporary Europeans regarded Avicenna and Al-Razi as the greatest authorities on medical matters, and portraits of both men still adorn the great hall of the School of Medicine at the University of Paris.

Thus, the Arab world not only provided a successful line of transmission for the medical knowledge of ancient Greece and the Hellenic world (late antiquity), it also corrected and enormously expanded that knowledge before passing it on to a Europe that had abandoned observation, experimentation and the very concept of earthly based life, centuries before. Physicians of different languages and religions had cooperated in building a sturdy structure whose outlines are still visible in the herbal and medical practices of our own time.

The herbal story goes of from here and I will write more essays to delineate this journey but as can be seen from this short essay on the history of medicine, we as herbalists are indebted to many people from different cultures, times, religions and regions of the world. To say ‘herbal knowledge was stunted in the Middle Ages’ or was terminated by the Inquisition, or was always shamanistic etc., is very shortsighted, incorrect and diminishing in its brevity and lack of scope. We have to be more educated in history to see that one part of the world may have become stagnant but other areas were in their glory.

What constitutes ‘Western herbalism’? Haven’t we been unwittingly practicing a form of ‘Planetary Herbology’ for centuries? (This term was coined by Michael Tierra over 20 years ago.) How many of our ‘Western herbs’ were really introduced centuries ago from far away lands? Our roots as herbalists did not die out because of the Dark Ages in Western Europe, nor were all the herbalist killed or tortured thus putting a damper on our herbal ways. Our roots grew deeper and richer with the critical (scientific) thinking, curiosity and intelligence of our Byzantine (Greek), Arab and Persian scholars. From these sources, European herbalism as we know it was born.

Where are the home lands of cinnamon, ginger, clove, nutmeg, fennel, oregano, rosemary, thyme, ginger, nigella, myrrh, and elecampane (elecampane for example is native to Central Asia and was introduced to Europe)? What would we do as Western herbalists if we did not have these medicinal plants from all over the world?

Due to our forgetfulness of our herbal roots and healing systems, I feel we have created limited philosophies around herbs, what we will or will not use and how we see ourselves in the historical context as herbalists. Our vision of ourselves as part of this multi-cultural heritage can help to expand and clarify our place in history and help us to be more open to new (and old ideas) of what it means to be an herbalist. We can embrace our history and not make up a history based on hearsay and rumors. We can see ourselves in the greater scope of the human endeavors for understanding our place in the world with one another and the plants.

Candis Cantin, AHG

January 26, 2009

Visit Candis at http://www.evergreenherbgarden.org/