Michael Moore, the great Southwestern herbalist of North America, left his earthly dwelling for other realms on Friday, Feb. 20, 2009. Michael leaves us a rich legacy of herbal knowledge and wisdom, the fruit of over 40 years of his passionate explorations of the fundamental healing relationship between plants, the earth and humankind.

I had first heard of Michael around 1967 when he and I were involved with the avant-garde music scene at UCLA. At the time, Michael was an accomplished symphonic trumpet player. True to his nature as one attracted to the more esoteric fringe aspect of any endeavor, Michael was not content to simply occupy a life chair in a symphony. Instead, he was well known as the unconventional musician who was open and willing to explore exciting new musical languages and artistic experiences.

It just so happens that when we had our first brief encounter at a rustic outdoor summer fair in Topanga Canyon between Malibu Beach and San Bernardino in Los Angeles, Michael was already involved in another fringe movement: herbal medicine.

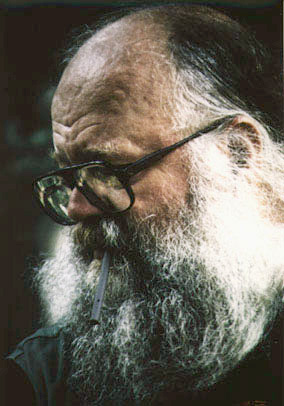

At the time I was identified with the artistic beat culture and living in Venice West. I must confess, herbs and herbal medicine had not even occurred to me when I happened into a quaint herb stall at the fair. Herbs hung to dry from the eaves and various homemade potions, lotions and ointments were priced to sell. For some strange reason I was drawn into this medieval-looking tableau and was taken a little aback to see a large man with a shaggy beard sitting behind a counter, looking more like an LA biker than ye olde herbalist of yore. We shared the look of the ‘beat outlaw,’ and as such we should have been kindred spirits, so to speak; yet, his eyes were fixed menacingly on me.

I never understood why until years later, when Michael explained that he remembered my wandering into his booth and that he was sure I had pilfered one of his herbal extracts. Well, in those days I might have, but hardly from him — I was still in my ‘rebel without a cause/Robin Hood’ period and I would hardly have stolen anything from someone who looked as disheveled as he did. I also distinctly remember that Michael was eager to tell people the then-revolutionary idea that herbs could heal body and soul, but few believed him, and it didn’t appear that he did much business. Given the social climate for herbs and my own ignorance at the time, I half jokingly reassured Michael, when we became respected herbal colleagues much later, that I owed him no debt from that day at the fair.

In retrospect, what I get from that brief encounter was that Michael Moore was pursuing his passionate affair with herbs before I or most anyone knew there even was such a thing (except, of course, for the herb). Years later we met again at a number of seminars and I visited his store Herbs Etcetera in Santa Fe. At the time he was teamed up with another giant man, Stuart Watts. Stuart and I were part of the first group of North American acupuncturists who went to China in the ’70s specifically to study Chinese herbal medicine, which was then pretty much unknown among non-Chinese in the West.

I remember how much Michael and Stuart resembled each other in stature but also in the incongruity of their appearance as healers. As I mentioned in my first impression of Michael above, you could easily have mistaken these two as members of a biker gang. The fact was, they were both at the top of their game. Michael was never much of a business man. Like the rest of us, he didn’t get involved with herbal medicine to get rich but was able to preach the gospel of herbs to anyone he encountered. From the beginning we were both dedicated to plying our herbal potions on those suffering from various ailments, who for a number of very good reasons found conventional Western medicine unsatisfactory. Michael mainly wanted to sell enough so he could continue his passion, which was to go either alone or with a small number of adventurous students on his herbal forays through the mountains, deserts, forests and canyons west of the Rocky Mountains. This was a perfect calling for Michael Moore, for various reasons.

You see, back in the ’70s (and even continuing up to the present day somewhat,) the extent of our knowledge of North American herbs might have been summed up with ginseng, goldenseal, sassafras and sarsaparilla, which grow east of the Rockies. This part of the United States was first to be settled, and it was settled at a time when there was a still a keen interest in herbs as healing agents both here and in Europe. In those days there was a lively exchange of information and many Eastern seaboard medicinal herbs were shipped off to be integrated into European medicine. The Chinese, hearing that wild ginseng was available, literally imported tons from Eastern forests so that the ‘seng’ trade rivaled the trade in furs and other wild products.

By the time the Westward expansion began to occur, interest in herbs – at least new herbs – was on the wane, and Native Americans, seeing how brutally their Eastern brethren were treated, became more and more reluctant to tell white settlers about the use of their native plants. So by the North American herbal renaissance in the mid-20th century, we herbalists knew little or nothing about native herbs west of the Rockies.

Enter Michael Moore, a man whose aerophobia kept him close to his Southwestern home base, and who loved to get in his truck and drive to remote areas of the West to learn, teach and harvest herbs for his homemade potions. Michael educated himself from whatever scientific literature was available, usually from “journals, sources and research outside the United States,” as he states in the introduction to his Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West. He expresses this frustration of not being able to find similar literature in his own country in one of his usual rants against the ‘establishment’: “We are able to develop and finance BIG medicines; we have no method of developing and financing little medicines (like herbs),” in contrast to countries like China and India, for instance.

Michael describes our being embroiled in a “grim, desperate, multi-billion-dollar mud-wrestling match between the public sector (the Food and Drug Administration) and the private sector (the pharmaceutical/medical/hospital industry).” He lays the problem out clearly, pointing out that the initial cost of $50 million is what it takes to bring a drug to market, meaning that no less than a million people a day have to take the new drug to justify its cost. It’s hardly any different today than it was in 1989 when this book was first published, except to say that the figure is probably much, much bigger.

Michael goes on to say that at the time of his writing, medicine was our biggest industry, bigger than the Pentagon, costing us 10 percent of our Gross National Product. That was then; today not only is medicine still our biggest industry, but its cost has grown to 17% of our gross National Product, according the National Coalition on Health Care. Is it any wonder that in these times of deep recession we read in the news about how herb and supplement sales are up?

No herbal reference library should be considered complete without Michael Moore’s three major books, Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West, Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West, and Medicinal Plants of the Pacific West. The first two are published by the Museum of New Mexico Press and the last by Red Crane Books. These are universally regarded as classics by the majority of herbalists throughout the world, not only for their practical descriptions of in-the-field, hands-on use of the herbs Michael selected, but also for his inimitable ‘Kerouacian’ witty writing style that makes his herb books a very special experience to read (a talent of which the rest of us who have written herb books can only be envious). Here is a link to all of his published books and clinical manuals.

In contrast to the lucid communication provided by his books, Michael had an eccentric, difficult to understand stream-of-consciousness style of teaching. He seemed to have such a uniquely consummate understanding of Western biochemistry and physiology that he couldn’t help but weave us dizzyingly through a labyrinth of complex scientific terminology and interrelationships in class. Few could follow him and still come out the other side; I know I couldn’t. But I could understand enough to know that Michael espoused a vision of holistic interconnectedness expressed in scientific terminology that completely jived with my traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic models. It may have been tough for us to hang on to Michael’s train of thought in a workshop or classroom situation, but this never diminished one iota my deep respect for him, whom I consider another one of those misunderstood geniuses.

For a while I wanted to engage Michael in a discussion comparing Chinese and Ayurvedic energetic herbal medicine with what I mostly suspected was Michael’s version of the same in Western biochemistry and physiology. Knowing this, he approached me with his intention to formulate a constitutional model of the human body based on Western physiology. We co-taught one class together on this. In the end, I’m not sure either of us nor any of the participants got anything from the experiment, but it is worth knowing that we tried and that this is now increasingly becoming a powerful direction in which to carry Planetary Herbology in the future.

I do know that despite his gruff appearance, Michael was a true gentleman. He was always too cognizant of his own personal shortcomings to hold anything against others he would encounter. I think the concept of the personal hamartia (the tragic flaw that ultimately brings down the hero that the audience perceives but the hero does not) didn’t apply to Michael, whose self-awareness made him the kind of teacher and healer who would have to say in so many words, “Do as I say but not as I do.” All of us have our personal limitations that we must struggle with through life. In Michael’s case these do not in the slightest tarnish the contribution he has made to herbalism now and as far as it will extend into the future.

Dioscorides, the famous Greek physician who served as a field doctor to Roman legions during the reign of Nero, discovered and chronicled the medical use of over 600 plants found throughout different regions of the known Western world. His herbal served as the most indispensible one of its kind for over 1,500 years through the Middle Ages. In a similar way, Michael Moore’s three books on the medicinal uses of herbs west of the Rocky Mountains will remain as the quintessential source reference for this area for many years to come.

But back to the burly, bearded, avant-garde musician-herbalist at the fair.

I have noticed that for the most part, herbalists in all cultures are also artists, musicians or poets. There is an appreciation for aesthetics and things beautiful and creative that I think underlies one’s attraction to the use of plants as medicine. As Michael says, “There are no fixed methods to apply to the human predicament, there is no single all-pervasive rule to follow, since medicine is not a science but an art.”

No matter how deeply one studies and enters into the complexity of healing, plant biochemistry and so on (and I happen to agree with Michael that one should go deeply into these things), nevertheless there is always place for the irrational and the subjective. The poet’s perspective of life, the musician’s sense of harmony, the artist’s eye of proportion and relationships – these are all shared by healers, especially the herbal healer who works with plants, which are the pure creative expression of nature and the healing process.

Michael was an extraordinary musician. Music is something that he and I shared in a special way. I was honored when at a symposium he presented me with a gift of two CDs which were the recordings of his beautiful orchestral works. After I learned of his passing, I went to find these CDs and play them in his honor. For whatever reason, they would not play. I was so happy to see that these recordings, along with his teaching manuals, scans of valuable medical Eclectic books, and other precious herb-related materials, are all freely available to enjoy online.

We are so blessed to have this kind of access to Michael’s herbal and artistic treasures, which he always so graciously shared. Personally I think this says volumes about the kind of man Michael Moore was: at the core of his being, he was a man of genius, deep caring and generosity.

![]()

Note: Michael’s generosity does not leave a whole lot to pay for his enormous medical bills and support his beloved wife, Donna. It is important that we give back some of what we received from the life work of Michael Moore and all that he has done for the herbal renaissance of North America. Donations can be made out to The Bountiful Alliance and sent to: Catherine Mackenzie, 457 East Riverside Dr., Truth or Consequences, NM, 87901. The Bountiful Alliance is a 501 C-3 non-profit organization and is able to issue receipts for tax purposes.

Please consider attending this April 17-19, 2009, event in Truth or Consequences, NM. Originally coordinated to help raise funds for Michael’s medical expenses, now it will be not only a fine educational event but also a celebration of this great herbalist’s life and legacy.