The meditation theme for today, the third day of Kwanzaa, is Ujima — Collective Work and Responsibility.

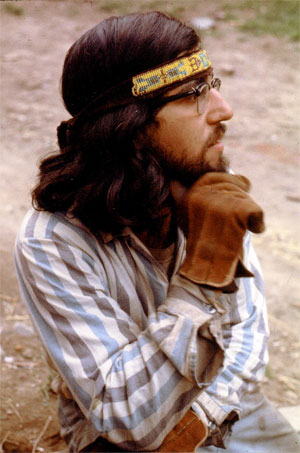

I can hardly reflect on this theme without considering my own experiences as a Digger — a hippie living in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury district from 1967-69. These years of my life, considered now the zenith of the hippie revolution, finally culminated with myself and others founding a wilderness community known as Black Bear Commune in the mountains of Northern California. (The photo below is one of a much younger me at Black Bear.)

During those years, thousands of young people throughout America found themselves smitten with the wanderlust for a new life purpose. This quest often used the promise of love, sex, and rock and roll as its rudder, but in the highest sense it was a search for community based on principles of “do-your-thing’ self-determination, sharing and openness — all based on what I generally believe to be a well-founded conviction in the essential goodness of humanity.

In my community we learned that it was possible to share so many parts of ourselves with each other — our homes, food, methods of transportation, bodies, minds, spirit, art, music and yes, even drugs — and no one would be the lesser for having participated. In fact, it was quite the opposite; we learned that by voluntarily pooling our resources we were greater than the sum of our proverbial parts. Then it dawned on us that with a cruel illegal Viet Nam war looming in the background, and the struggle for racial and gender equality raging on all around us, we were participating in a movement that was soon seen as a threat to the principles of a society and politic that was antithetic to our young ideals. We aimed to build a culture and community counter to a society that sought to control individuals by keeping “we the people” separate and alienated from each other.

The fact is that in our time, there is more than enough of all the necessities to go around. We could feed thousands at a love-in in Golden Gate Park by barbecuing the meat of a freshly dead whale from a marine biology lab up the Northern California coast. The still very edible discarded unsold produce that filled the waste bins behind giant supermarkets was practically enough to feed a community of large multiple dwelling homes in the Haight. With the spirit of sharing openness on the part of its legal owners, one truck that would otherwise spend most of its time unused and parked on the street was used to pick up and deliver these and other useful goods to the places where they were needed. What’s more, it was all done in a spirit of goodwill and joyous satisfaction. It was a “thing” that someone was eager and happy to do, and others were able to benefit from this union of generosity, joy and action. There was nothing to steal or take because whatever there was belonged to all.

In short, it was the picture of ujima — all of us took reponsibility for one another and worked collectively to achieve a harmonious community.

Foreseeing the collapse and devolution of the hippie/Haight Ashbury culture (which was partially because the media kept blowing it up and inevitably more and more unsavory elements mixed with drugs took its toll,) I and some friends purchased land in the Klamath mountains with a down payment provided from various “weekend warrior” Hollywood and rock band types. In the autumn of 1968 about 30 of us moved out onto the land, named Black Bear Ranch. At first it truly represented our “back to Eden” mythos. It was a place with two year-round running creeks you could drink and fish from, endless miles of national forest (these were the days before the U.S. Forest Service designated such wild tracks as “tree farms”), no electricity or telephone, and a few broken down shacks. By the time we got there, we had barely enough time to truck in a winter’s store of food and put up a pile of wood for to provide heat for the next six months or so. We soon learned the value and meaning of interdependent survival, making the most of our collective pool of scant experience and whatever tools we could find.

This is where I seriously began to explore the wild plants and other possible sources for food and medicine we could derive from our natural surroundings. The goal was ultimately to become completely self-sufficient and freed as much as possible from a money-based economy. Even then we sensed the fall of the American capitalist empire (which may or may not be occurring at this very moment).

In any case I learned many powerful and valuable lessons about collective consciousness from that wilderness experience — life lessons that few of us living in our ticky-tacky little separate boxes we call home might hope to earn. We really are a tribal people and when we find ourselves in close daily intimate contact with a group of people based on interdependent survival, everyday life events and people assume mythic proportions. People tend to fulfill certain needed roles in a society if they are left to sort things out on their own as opposed to being told what niche to fill. I gravitated toward the herbalist, healer, and shaman; others became the kid care people; others, the garden care people, the animal care people, the art people, the kitchen people, the construction and repair people – all of this just naturally occurred without any pre- agreed upon assignments. Again, it was the power of “do your own thing” in action. For me it seemed uncanny but strangely natural. What’s more, we each eventually grew to resemble the various gods and goddesses of ancient mythology, and I learned first-hand how those myths evolved.

Another valuable thing I learned was that sharing cooperatively was the most ecological and economical way to live. We only needed one or two vehicles for the ranch, one being a mandatory truck. People shared tools and learned to maintain them for each other. I learned how natural it is that around the early spring, living off the land, one naturally gets low on animal protein and we just naturally eat less and shed the winter stores of fat. I also learned that living off the land as a vegetarian was, practically speaking, impossible. Our life together as a wilderness tribe convinced me that we are first a hunter/gatherer people, requiring fish and game to survive, along some wild edible plants which were the first to appear in the early spring. Living off the land as we did, we watched a agrarian lifestyle naturally arise with goat and cow’s milk, but we also relied for food on fish (salmon were abundant in the nearby rivers and creeks), deer and even an occasional bear or mountain lion.

(By the way, if you want to see a video that only hints at what communal life was like at Black Bear Commune, I suggest you rent the documentary “Commune” which I’m told is now the fifth top-rented Netflix film.)

So on this day of Kwanzaa and the next, let us meditate on our primal roots as an interdependent people, reliant on the earth and all its gifts and changes, but more importantly, each other. Consider the opposite: how utterly difficult it would be to have to survive totally by ourselves! The relationships and societies we create are not only to generate rivalry and confusion but also to at least make it possible for each of us to achieve a level of self-sufficiency so that a few of us at least can rear our very inquisitive heads above the herd to see and help prepare for what’s ahead — and yes, most importantly, to inspire us to a vision of unity.

Collective Work and Responsibility: “I Hear American Singing” by Walt Whitman

The poem for the today’s theme of ujima is by one of my all-time favorite poets, Walt Whitman:

I Hear America Singing

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,

Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand

singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter’s song, the ploughboy’s on his way in the morning,

or at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work,

or of the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day- at night the party of young

fellows, robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

Marijuana

Hydrastis

Herbs for Ujima: Marijuana and Goldenseal

My choice of herbs for our theme today is informed by my personal experience: Marijuana and Goldenseal. These were two of the most influential and widely used herbs during the inception of the Black Bear wilderness community (and by hippies in general).

If truth be known, the mid-20th century herbal movement was begun with marijuana — and we did happily inhale. Marijuana is currently finding deserved appreciation not only by those who use it recreationally but from the medical community. While frequent use of marijuana leads to a state of apathy and delusion which is counterproductive to health and well being, marijuana and all intoxicating herbs have and continue to play a vital role in human society — as a way breaking free of our stuck fixations, compulsions and obligations enough to see that somehow there are always at least several different realities operating or possible at any given time. In other words, we should always remember that we always have a choice. Ever notice how things tend to work themselves out whether we choose to play an active role or not? (For an illustration of this, I highly recommend that you rent the old 1938 Frank Capra movie masterpiece, “You Can’t Take It with You.”)

Goldenseal is an intensely bitter herb so that indeed it tends to serve as the “bitter brew” that serves as an antidote to our overindulgences that lead to liver congestion, toxicity, and stagnant inflammatory diseases.

The hippie bibles included the books “Stranger in a Strange Land” by Robert A. Heinlein and “Back to Eden” by the naturopathic doctor Jethro Klos. Jethro Klos was big on the use of goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) and until I rediscovered echinacea, it was the go-to herb for all infections and inflammations. It is still pretty good for those conditions taken both internally in a powder (usually put into gelatin capsules) and applied externally to infected sores and wounds. With herbalism going mainstream we have learned that the wild stands of North American goldenseal are endangered and so we should generally insist on using only organically cultivated goldenseal.