Pianos…

I’m in Fort Worth right now, at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. As a classical pianist, the opportunity to attend the Van Cliburn is akin to being able to attend a Super Bowl playoff. It’s especially a kick for me, because one of the contenders happened to be my son, Chetan Tierra, who was specially selected and auditioned from a worldwide pool of over 1,000 very talented young men and women. Despite being a favorite of the Dallas Star’s classical music critic and many of the audience, Chetan did not advance to the semifinals. The fact is, at such a prestigious, well funded and expertly organized event, all the contenders were among the best and most talented young pianists in the world today, and it’s a significant accomplishment to just be one of the competitors.

At the time of this writing, the Van Cliburn is in its final rounds with playoffs by the six finalists consisting of a 50-minute solo recital and two major concerto performances with orchestra. At least from my perspective, having met many of the avid Cliburn patrons, this is one of the most anticipated cultural events of this wonderful city. Many have assiduously followed the event, which has taken place every four years since its inception in 1962.

The competition is held in honor of Fort Worth’s very own esteemed resident Van Cliburn, who, at the age of 23, played the Tchaikovsky concerto at the Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in Moscow in 1958 — and won. Unintentionally, this put a chink of human warmth in the midst of the Cold War deadlock between Russia and the United States, which portended mutual annihilation at that time. Van Cliburn, then a tall, lanky red-headed boy from Texas, instantly became the beloved of both the American and Russian people. His win was no mean feat in the eyes of the Russians, who could not imagine that anyone who was not Russian could give a more powerfully passionate performance of Tchaikovsky’s iconic piece than one of their own.

Allow me to heartily recommend that you tune into the Van Cliburn website where you can watch incredible performances by Chetan and the other competitors.

Plants…

Plants…

As much as I am a musician, I am also an herbalist, so plants can never be too far from my range of experience, wherever I may be. To wit: I visited Fort Worth’s Botanical Research Institute of Texas (also known as “The BRIT”), which I learned was the country’s 10th-largest herbarium and the repository of over a million dried plant specimens in special storage cabinets dating as far back as 1741.

Few people who may have enjoyed pressing a favorite flower in a book or with guidance using a plant press in childhood, may ever have imagined that there exist multifloor herbaria dedicated to collecting and maintaining such fragments, along with information about the collector, the date and time of collection, and so forth.

The obvious question is: What purpose do these herbaria serve, especially in the 21st century age of information? Our guide, botanist Triana Franklin, said that such institutions as the BRIT serve many research-related functions, including charting the changing ecology of different regions and having an actual dried specimen of a plant that can be referred to in various botanical research projects involved with plant taxonomy, geographic distribution, and the standardizing of plant nomenclature.

In fact, most universities maintain herbariums. The most notable ones in the United States are the Gray Herbarium at Harvard and those at the U.S. National Museum (of the Smithsonian Institution) and at the New York and Missouri botanical gardens.

The herbarium at the BRIT has particular strengths in the plants of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Alabama, Tennessee, and all of the Gulf Coast and southeastern United States. However, its collections are also worldwide in scope, and most of the Earth’s plant families are represented here with special collections of plants from the Phillipines and New Guinea.

One of the distinctions of the BRIT herbarium is that it has one of the largest collections of plants in the Asteraceae (formerly Compositae) family. In common parlance, these are plants with ray-like flowers. From daisies to sunflowers to dandelions, this is one of the most ubiquitous plant families and is responsible for a certain percentage of allergic reactions. According to the curators of the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, the Asteraceae family comprises more than 1,600 genera and 23,000 species, enough to fill a modest herbarium, but not enough to fill the mighty BRIT.

We visited the room where new plant specimens are sent in daily and are handled and catalogued by volunteers specially trained by the national Master Gardener Program or the Texas Master Naturalist Program. Individuals participating in these programs volunteer their services a the BRIT Herbarium for credit, making it particularly useful when weather does not permit them to be exploring outside.

We visited the room where new plant specimens are sent in daily and are handled and catalogued by volunteers specially trained by the national Master Gardener Program or the Texas Master Naturalist Program. Individuals participating in these programs volunteer their services a the BRIT Herbarium for credit, making it particularly useful when weather does not permit them to be exploring outside.

Plants are pressed, dried and catalogued by volunteers, ideally following what the herbarium hopes might one day be a standardized catalogue methodology. However, with the recent taxonomic reclassification that is going on as a result of DNA typing, the task of not only renaming but recataloguing bits and pieces of dried and pressed plant material dating back over 400 years is bound to remain an herbarium’s distant dream for many years to come. Displaying all their respective parts (leaves, stalk, flowers and root), plants are laid out and pressed on non-acidic paper or fastened by special glue strips that will not degrade the plant material. Also recorded and preserved with the plant specimen are the standard Latin binomial genus and species names, plus the name, names or initials of those individuals who assigned the name to the plant.

For both edification and fun, check out the following page on the taxonomy of echinacea to find out just how complex plant taxonomy can be.

(Pictures above from http://www.brit.org/herbarium/.)

And Pests!

And Pests!

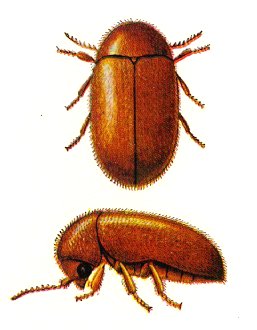

For what it’s worth, particularly to my fellow herbalist colleagues and students, I finally got to identify one of the most common insect pests that have been a nuisance at my herb pharmacy for years. Unsurprisingly, it also plagues herbaria and is aptly named the “herbarium beetle” or “cigarette beetle” (Lasioderma serricorne; Coleoptera, Anobiidae). I think we can also safely call it the “herbal pharmacy beetle.”

I also found out that the herbaria practice the same method of extermination as I do. Not wanting to discard plant specimens that are hundreds of years old, herbarium staff simply place them into a -40 degrees F freezer for four days, shake off and discard the dead beetles, and return the plant to its proper shelf location. For a more up close and personal description of this little harmless critter which may actually be one of the best natural sources of B12 and other nutrients (I know you avid vegetarians and vegans will love that!) go http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IG116 here.

Fort Worth also has several wonderful museums including the Modern Art Museum, Kimbell Art Museum and the Amon Carter Museum, all very worth a visit. Fort Worth also has a beautiful botanical garden. Triana and the staff of the BRIT Herbarium are anxiously awaiting with a mixture of anticipation and some dread (at the work involved), a move away from the busy financial district to a location appropriately adjoining the botanical garden.

Visit the BRIT’s website here or drop by for a visit the next time you’re in Fort Worth.

The Van Cliburn competitions are awesome, Michael; I hope your son plays well. Pretty amazing accomplishment even to be selected for this. Good luck tomorrow!